The Birth of the “Dilbert Dunker”

Whether they loved it or hated it, the thousands of naval aviators who rode the “Dilbert Dunker” owed the experience to a Massachusetts Institute of Technology engineer.

Although it was Hollywood that introduced the device to the general public in the motion picture An Officer and a Gentleman, for generations of naval aviation personnel the “Dilbert Dunker” that sent them plummeting into a pool during water survival training was a rite of passage. Whether they enjoyed the ride or dreaded the experience, everyone who took the plunge owed this aspect of their training to a World War II era Massachusetts Institute of Technology engineer.

The prospect of making a forced landing at sea is a real possibility for every naval aviator who has ever climbed into a cockpit all the way back to Lieutenant Theodore G. Ellyson, the Navy’s first aviator. On July 31, 1912, during experiments with an early catapult system at Annapolis, Maryland, the A-1 Triad that Ellyson was flying reared up and was caught in a crosswind, sending him and the airplane plunging into the Severn River. Yet, during naval aviation’s earliest years, naval aviators could take comfort in the fact that the sea service primarily operated seaplanes and flying boats that were equipped to land on water. That began to change in 1919 when the Navy employed surplus foreign-built World War I era fighters in experiments operating wheeled aircraft from temporary wooden flight decks erected on battleships. Expecting some of them have to ditch in the water, the Navy installed equipment on the planes in the event of such an occurrence, including a hydro vane fitted forward of the landing gear to prevent the plane from nosing over on impact and flotation bags beneath the wings that the pilot would trigger in order to keep the plane afloat long enough for it to be salvaged.

As evidenced above, while there was great interest in preserving the aircraft, there was no specialized training for the pilot, even into the early months of World War II. At the Battle of Midway, a number of F4F-4 Wildcat fighters from Fighting Squadron (VF) 8 off the carrier Hornet (CV 8) were forced to ditch because of lack of fuel. The after action report filed by one pilot, Lieutenant (junior grade) John Magda, later a flight leader of the famed Blue Angels, contained the following suggestion. “There should be a landing in water ‘check-off list’ in every plane, because at a time like that there are a few things you may…forget that prove to be a very dear mistake. There is very little time to do anything after the plane hits the water—thirty seconds at the most.” Lieutenant (junior grade) H.L. Tallman, another VF-8 pilot, wrote, “Shock of landing is not bad, but the water that gushes into [the] cockpit and the splash caused by the impact leads one to believe at the moment that the plane is going right on down. Actually, by the time you’ve recovered your senses (1-2 seconds) the water is up to your neck.”

As evidenced above, while there was great interest in preserving the aircraft, there was no specialized training for the pilot, even into the early months of World War II. At the Battle of Midway, a number of F4F-4 Wildcat fighters from Fighting Squadron (VF) 8 off the carrier Hornet (CV 8) were forced to ditch because of lack of fuel. The after action report filed by one pilot, Lieutenant (junior grade) John Magda, later a flight leader of the famed Blue Angels, contained the following suggestion. “There should be a landing in water ‘check-off list’ in every plane, because at a time like that there are a few things you may…forget that prove to be a very dear mistake. There is very little time to do anything after the plane hits the water—thirty seconds at the most.” Lieutenant (junior grade) H.L. Tallman, another VF-8 pilot, wrote, “Shock of landing is not bad, but the water that gushes into [the] cockpit and the splash caused by the impact leads one to believe at the moment that the plane is going right on down. Actually, by the time you’ve recovered your senses (1-2 seconds) the water is up to your neck.”

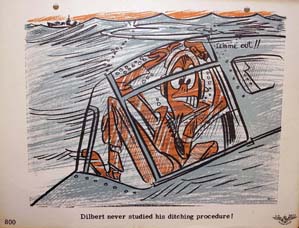

While words could convey some guidance on ditching at sea complemented by coverage of the subject in the popular Dilbert posters and “Sense Pamphlets” introduced during the war, the Navy realized that there was a need to simulate the experience during training. Enter Ensign Wilfred Kaneb, who received his commission in the Naval Reserve in March 1943, as an A-V(S), the wartime designation for an aviation officer qualified for specialist duties. His orders soon directed him to Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola, where he was tasked with putting his engineering knowledge to work developing a training device to, as Kaneb remembered one senior officer commenting, “Teach them what it is like to be drowning.”

With all due respect to that officer, Kaneb’s objective was not to simulate drowning, but to teach the trainees to orient themselves underwater, though even he later recalled that this was accomplished with “water in every sinus” of those under instruction. Setting to work, Kaneb led a team of engineers in developing a mock-up of what he called the “Underwater Cockpit Escape Device.” Borrowing the name from the cartoon character of an aviator who never did anything right that was featured in training literature, the device was from its earliest days called the “Dilbert Dunker.”

With all due respect to that officer, Kaneb’s objective was not to simulate drowning, but to teach the trainees to orient themselves underwater, though even he later recalled that this was accomplished with “water in every sinus” of those under instruction. Setting to work, Kaneb led a team of engineers in developing a mock-up of what he called the “Underwater Cockpit Escape Device.” Borrowing the name from the cartoon character of an aviator who never did anything right that was featured in training literature, the device was from its earliest days called the “Dilbert Dunker.”

In an April 12, 1944, letter to the Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics describing the device, the commanding officer of NAS Pensacola wrote that the “Dilbert Dunker” was “an attempt to simulate an actual water crash landing in which the aircraft somersaults and sinks, and from which the pilot must free himself in the most expedient manner.” In order to make the training as realistic as possible, the original dunker featured the surveyed forward fuselage section of an SNJ Texan that contained “all equipment in the cockpit that would hinder a pilot’s exit from the cockpit.” This included the instrument panel (minus the instruments themselves) and the stick, rudder pedals, and brake pedals, which were spring loaded to simulate actual conditions by holding them in place. In operation, the “Dilbert Dunker” rolled down a track at a 45 degree angle, reaching a speed of 25 miles per hour when it hit the water and overturned, coming to rest underwater in the inverted position.

Kaneb’s design appeared at Pensacola and other locations in the training command, each device handmade and individually tested. The opinions of those who rode it were captured in a September 1944, article in Naval Aviation News. “First trippers usually register fear, but a survey of ‘veteran’ dunkers showed recently that out of 311 riders, 306 expressed approval of the device as an aid in training them how to get out of a cockpit.”

Kaneb’s design appeared at Pensacola and other locations in the training command, each device handmade and individually tested. The opinions of those who rode it were captured in a September 1944, article in Naval Aviation News. “First trippers usually register fear, but a survey of ‘veteran’ dunkers showed recently that out of 311 riders, 306 expressed approval of the device as an aid in training them how to get out of a cockpit.”

The “Dilbert Dunker” was not the only method of water survival training to appear during World War II and afterwards. In both the Navy and Army Air Forces, fuselage sections of aircraft like the B-29 Superfortress and TBM Avenger were dropped into the water with crews aboard for the purpose of instructing them on each man’s tasks as they exited the airplane, especially retrieving life rafts. Today, a helo dunker provides underwater egress training for rotary-wing platforms. As for the “Dilbert Dunker,” it lives on only as an artifact in the museum collection and in the memories of those who trained in examples of the device during their days in naval aviation, from aviation cadets to astronauts.

(Some of the background material for this article came from the Wilfred Kaneb Papers, which he recently donated to the museum. Now over ninety years old, the inventor of the “Dilbert Dunker” lives in Ontario, Canada.)