Naval Aviation and the Search for Amelia Earhart

In July 1937, U.S. Naval Aviation played a major role in the wide-ranging but ultimately fruitless search for famed aviatrix Amelia Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan.

Amelia Earhart was one of the stars that sparkled in the Golden Age of Aviation and her disappearance in July 1937, has remained one of history’s enduring mysteries. Now, as The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) mounts an expedition to the island of Nikumaroro in an attempt to find the wreckage of her aircraft, it is fitting to look back at the U.S. Navy’s attempt to find her and her navigator Fred Noonan.

On July 2, 1937, having earlier in the day taken off from Lae, New Guinea, Earhart and Noonan’s Lockheed Electra made final radio contact with the Coast Guard Cutter Itasca, which lay at anchor at their intended destination of Howland Island. When efforts on the part of personnel on board the cutter to contact the airplane proved fruitless, she got underway, commencing one of the greatest air-sea searches in history, which quickly involved the U.S. Navy. While Itasca set out to search by sea, Lieutenant Warren W. Harvey and his crew manned a PBY Catalina and took off from Hawaii bound for Howland Island, adverse weather conditions forcing them to abort their search efforts and return to Pearl Harbor. By that time, the Navy had ordered the battleship Colorado (BB 45), already in Hawaii for an indoctrination cruise for ROTC midshipmen, to provision and depart for the vicinity of Howland Island, which was located over 1,600 miles from Honolulu. It joined the small seaplane tender Swan (AVP 7), which had been dispatched to Howland Island to support seaplanes that could be called into action to search.

On July 2, 1937, having earlier in the day taken off from Lae, New Guinea, Earhart and Noonan’s Lockheed Electra made final radio contact with the Coast Guard Cutter Itasca, which lay at anchor at their intended destination of Howland Island. When efforts on the part of personnel on board the cutter to contact the airplane proved fruitless, she got underway, commencing one of the greatest air-sea searches in history, which quickly involved the U.S. Navy. While Itasca set out to search by sea, Lieutenant Warren W. Harvey and his crew manned a PBY Catalina and took off from Hawaii bound for Howland Island, adverse weather conditions forcing them to abort their search efforts and return to Pearl Harbor. By that time, the Navy had ordered the battleship Colorado (BB 45), already in Hawaii for an indoctrination cruise for ROTC midshipmen, to provision and depart for the vicinity of Howland Island, which was located over 1,600 miles from Honolulu. It joined the small seaplane tender Swan (AVP 7), which had been dispatched to Howland Island to support seaplanes that could be called into action to search.

Colorado carried three O3U Corsair observation floatplanes, which on July 7th began conducting aerial searches for the downed fliers. At the controls were three naval aviators, Lieutenants L.C. Fox, W.B. Short, Jr., and J.O. Lambrecht, the latter the senior aviator on board the battleship. His report of the searches noted that they were carried out at an altitude of 1,000 ft. with visibility and sea state such that he considered it possible to see a raft from a distance of five miles. Colorado‘s aircraft ended their search efforts on July 12th, having flown 21.2 hours and 1908 miles each. All told, Colorado with her planes covered within the radius of visibility an area of 25,490 square miles.

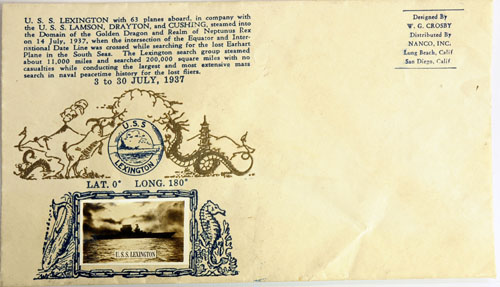

In the meantime, the Navy had ordered the aircraft carrier Lexington (CV 2), which in 1928 had set a speed record between the West Coast and Hawaii, to make a high speed run to the search area. Carrying sixty-three aircraft, the carrier offered the prospects of greatly expanding the search area, one newspaper proclaiming in a headline “Lexington Holds Fate.” The Oakland Tribune reported, “Naval authorities say that the chance of finding the two fliers will depend upon the systematic search to be made by the armada of planes from the Lexington to be developed over a rectangle of sea approximately 600 miles by 400 miles.”

In the meantime, the Navy had ordered the aircraft carrier Lexington (CV 2), which in 1928 had set a speed record between the West Coast and Hawaii, to make a high speed run to the search area. Carrying sixty-three aircraft, the carrier offered the prospects of greatly expanding the search area, one newspaper proclaiming in a headline “Lexington Holds Fate.” The Oakland Tribune reported, “Naval authorities say that the chance of finding the two fliers will depend upon the systematic search to be made by the armada of planes from the Lexington to be developed over a rectangle of sea approximately 600 miles by 400 miles.”

Lexington assumed control of the search for Earhart and Noonan on July 12th, shifting focus to the waters north and west of Howland Island. As the carrier’s planes searched, hopes began to diminish, a July 15th newspaper headline telling readers, “Chances of Finding Pair Placed at One in a Million.” Three days later, with carrier aircraft having covered thousands of square miles, search efforts were suspended. Wrote a sailor on board Colorado, “I don’t think they will ever be found for we searched the most likely area.” For the past seventy-five years, his assessment has remained true.