The N-9 Trainer

When the United States entered World War I, the Navy’s aviation resources included 300 officers and enlisted men on duty and just 58 aircraft of all types. Among the assortment of flying machines was the N-9. It served as the platform for the training of the World War I generation of aviators as well as the postwar junior officers of the 1920s. As senior officers, the latter led naval aviation to victory in a another global war.

An early N-9 pictured at NAS Pensacola. This airplane, Bureau Number A-365, was shipped to NAS Pensacola on December 1, 1917, and operated at the station until crashing in August 1919.

The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor delivered the N-9 as a seaplane version of the company’s successful JN Jenny. First flown in November 1915, it featured a single pontoon float, whose weight necessitated an extension of the lower wing from that on the landplane JN. In operations, Navy personnel found that this weight only increased as the pontoon became waterlogged, affecting the airplane’s performance.

The Navy expressed its first interest in procuring the N-9 in August 1916. The first of 531 examples entered service beginning in November of that year. Following U.S. entry into World War I, Curtiss subcontracted the design out to other manufacturers, including the Burgess Company in Marblehead, Pennsylvania. Resourceful sailors at various air stations also used spare parts from crashed N-9s to manufacture additional airplanes. The types evolved in its design. The nose radiator on the early versions gave way to a distinctive tower radiator placed atop the fuselage in front of the wing on the N-9H. This later version also featured a 150 horsepower Hispano-Suiza engine, a boost in power over the original 100 horsepower Curtiss OXX engine.

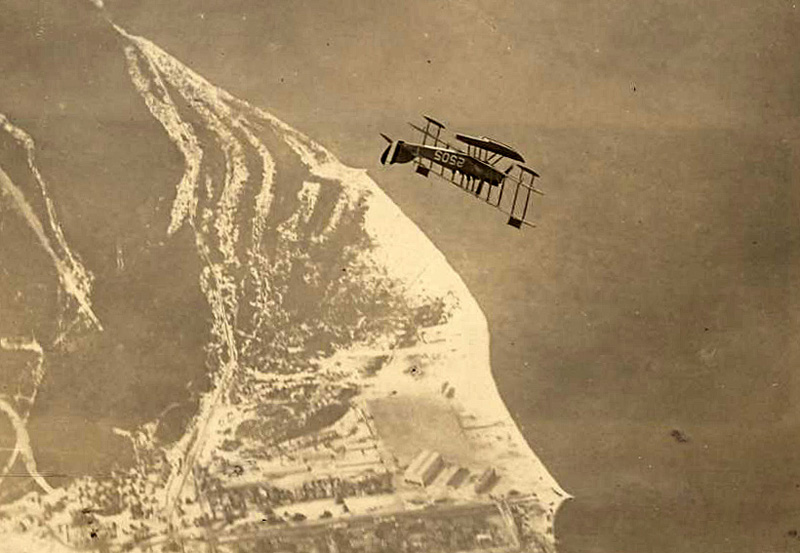

An N-9 seaplane picture in a loop over Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola, Florida, during 1918-1919.

Looping the Loop

Shortly after initial delivery, the N-9 made a name for itself in performing a first in naval aviation history.

On February 13, 1917, Marine Captain Francis T. Evans took off at NAS Pensacola in an N-9 to attempt to loop. As a publication of the time recounted, the flying leatherneck “astonished the officers at the aeronautical station…who had considered the feat impossible.” The reason behind their disbelief was the fact that Evans flew a seaplane with an elongated pontoon beneath the fuselage for water take offs and landings. Thus, conventional wisdom held that though a loop was no longer a novelty in wheeled aircraft, the weight of the pontoon on a seaplane would prevent it from achieving enough speed to complete a loop. To this end, as the same publication reported, “Captain Evans found it necessary to drive through the air at great speed before he could gain the inverse position. He then looped-the-loop twice before his descent.”

The letters of aviators from the era include descriptions of flying the N-9. “The type of plane we use is fitted with a light pontoon, and we take off and land upon the water,” a young officer wrote to his father from NAS Pensacola. “They are very strong planes, but not very fast or easy to handle. You must exert yourself constantly to keep them in the air.” Another recorded the thrill of following in Captain Evans’ footsteps performing a loop. “I did not get over the top, but hung upside down for a while as I did not have enough speed. It was something to look up and see the station above me…when the plane is upside down the engine stops with a putt putt bang bang. Then when going into the dive the motor comes on with a brrrr.”

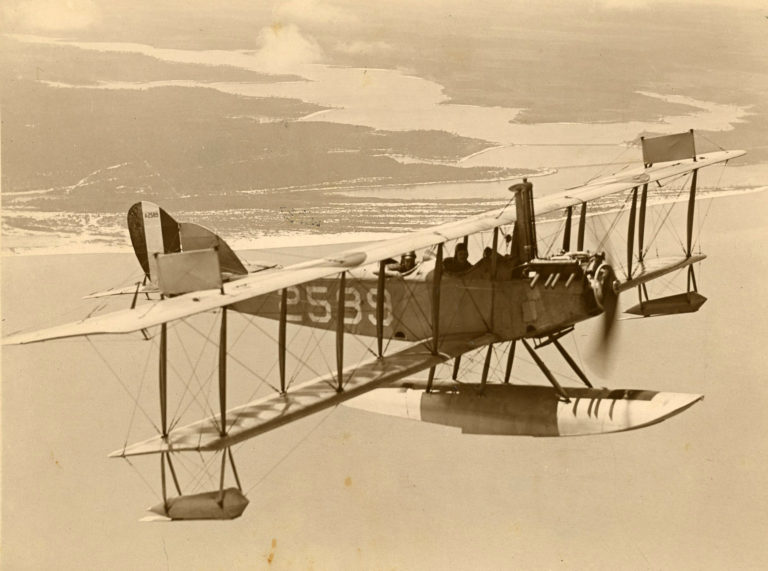

An N-9 pictured during a training flight near NAS Pensacola. Note the tower radiator visible forward of the upper wing. Arriving at NAS Pensacola in December 1918, this particular airplane was damaged on three occasions and repaired before it spun into the water in 1921.

A Versatile Platform

In addition to its training role, the N-9 participated in operational experiments during the formative era in which it served. This included service as a platform for bombing tests at the Naval Proving Ground in Indian Head, Maryland. Tragically, during one flight a bomb detonated prematurely, blowing the tail off the airplane. The subsequebt crash into the Potomac River killed Lieutenants Clarence Bronson (Naval Aviator Number 15) and Luther Welsh. Fitting N-9s with automatic control equipment, Navy personnel tested them as flying bombs, the foundation of modern guided missiles. Additionally, in 1919, an N-9 successfully launched from a motorized sea sled. The invention, the brainchild of Captain Henry Mustin during the Great War, was envisioned as a means of delivering aircraft to a range from which they could strike German submarine pens. Too late for employment in combat, the effort formed part of the evolution in thinking that led to aircraft carriers in the U.S. Navy. The N-9 also contributed to the testing of another application designed to take the airplane to sea, successfully launching from a compressed air turntable catapult in October 1921.

The N-9 last appeared in the Navy’s aircraft inventory in 1928, its appearance in the log books of thousands, testament to its important role in shaping U.S. naval aviation.